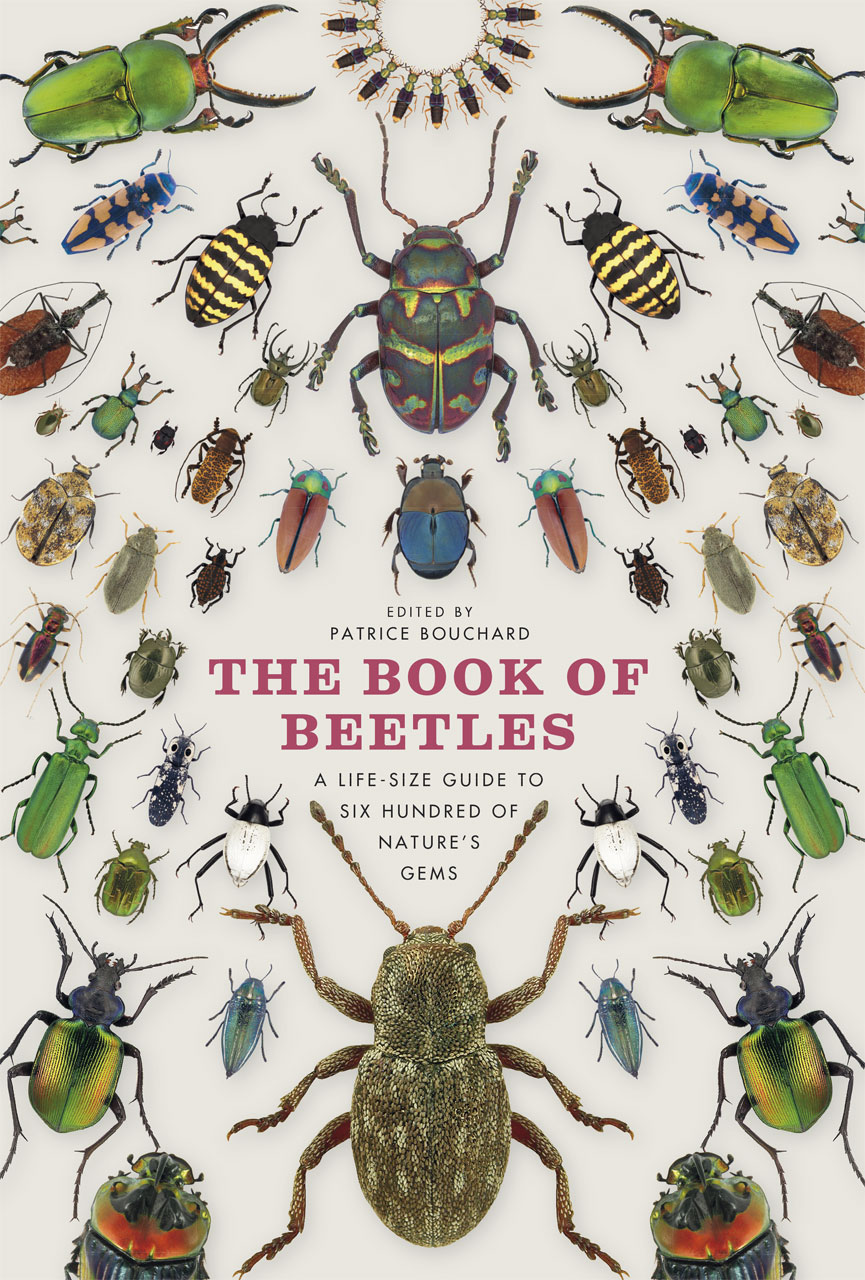

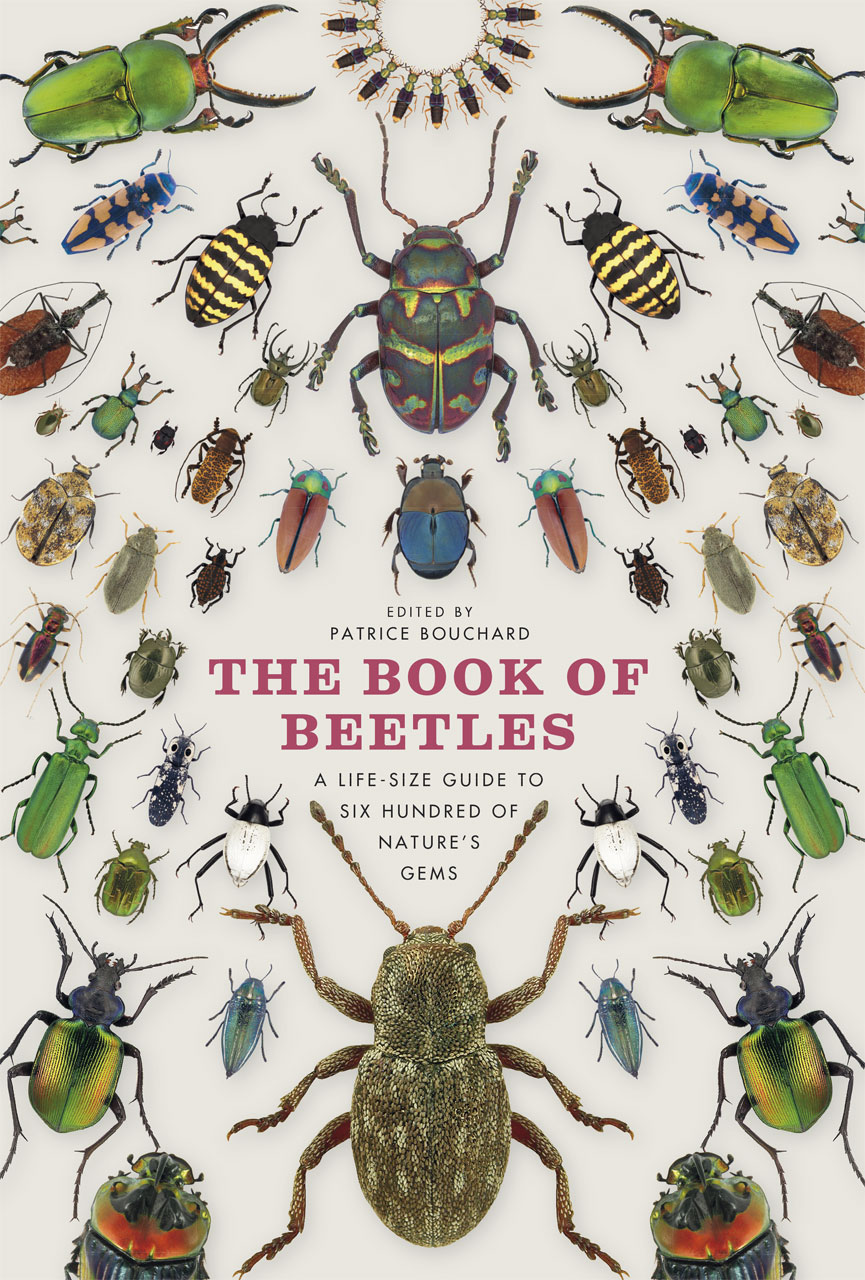

The Book of Beetles: A Life-size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature’s Gems

The Book of Beetles: A Life-size Guide to Six Hundred of Nature’s Gems

Edited by Patrice Bouchard

Contributions by Patrice Bouchard, Yves Bousquet, Christopher Carlton, Maria Lourdes Chamorro, Hermes E. Escalona, Arthur V. Evans, Alexander Konstantinov, Richard A. B. Leschen, Stéphane Le Tirant, and Steven W. Lingafelter

2014, University of Chicago Press

656 pages, 2400 color plates

$55 (cloth), $33 (eBook)

Last autumn, while I was wandering around the poster presentations at the Entomological Society of Canada annual meeting in Saskatoon, I came across very inconspicuous display highlighting a book that was about to be released. Inconspicuous or not (and “display” might be a generous word to describe what simply amounted to a pile of handouts on a side table), it immediately caught my eye. And why wouldn’t it? The subject, beetles – in all of their glorious shapes, sizes, colors, and life histories – is always eye- and mind-catching. Upon returning home, I immediately pre-ordered it and received it from my local bookstore shortly after it was published. It has taken residence on the coffee table in our living room, and I have been enjoying it ever since.

The book is simply titled “The Book of Beetles” and is edited by Dr. Patrice Bouchard (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) with contributions by a number of experts. Much like “Snakes on a Plane”, the title tells you what it is about. But unlike that movie, this book is much more than its simple title. The idea of covering the full diversity of beetles sufficiently is, of course, a pipe dream. This book runs over 650 pages and covers 600 of the hundreds-of-thousands of known, not to mention the likely millions of more unknown, species of beetles. The full spread of beetle diversity is immense and, as is pointed out in a brand new (and open access!!) paper, “The beetle tree of life reveals that Coleoptera survived end-Permian mass extinction to diversify during the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution” by McKenna et al., “…(beetles) account for ∼25% of known species on Earth and ∼40% of insects”. To cover every known beetle species on earth would require well over 600 more of these volumes.

Also from McKenna et al.:

Curculionidae [snout and bark beetles, commonly referred to as weevils or “true” weevils] is the second most diverse family of metazoans (surpassed only by the rove beetle family Staphylinidae, which is older) with more than 51 000 named extant species in more than 4600 genera. Conservatively, it is estimated that there are more than 200 000 additional undescribed species of Curculionidae alone.

In other words, if we knew every single species of weevil extant today, we would need to compile more than 400 volumes of this size just to cover that one group within the beetles.

So the authors the The Book of Beetles were obviously required to complete the daunting task of choosing a mere 600 beetle species – a bit more than 0.1% of known beetle species – to highlight in this book.

In the introduction the authors set out their criteria for inclusion in this book. The authors chose among beetles that, variously:

- are “scientifically compelling”

- have “curious natural histories”

- are “culturally significant”

- are “economically important

- are “rare and threatened”

- are “physically impressive”

Again, certainly many, many other beetle species besides the chosen 600 met all of these criteria but could not be included. But I would argue that the editor and contributors did a fantastic job of selecting 600 compelling examples of these amazing insects that highlights a small, but still immense, range of their diversity.

Upon first encountering this large book (the cloth version, weighing in at 2.2 kg, is not one that is easily read in bed, but there is also an eBook option for those so inclined), the reader is immediately struck by the beauty of the jacket featuring an array of impressive insects surrounding the title. Remove the dust cover, and you will find three more gorgeous photographs of beetles on the front, spine, and back. These photographs all should simply whet your appetite for what you will find when you open the book.

The book begins with a short introduction to the volume followed by eight nicely illustrated chapters entitled “What is a beetle”, “Beetle classification”, “Evolution and diversity”, “Communication, reproduction, and development”, “Defense”, “Feeding behavior”, “Beetle conservation”, and “Beetles & society”. Each chapter is accessible for the non-expert, but engaging and full of enough detailed information to also keep career entomologists and expert naturalists interested. The chapters are short, ranging from about two to six pages each; and by p.30 the real meat of the book – the description of the 600 chosen beetle species – begins. The book, at this point, is divided up into four parts covering species from the Archostemata, the Myxophaga, the Adephaga, and the Polyphaga. The latter, of course, comprise by far the largest portion of the book

If you want to take a good look at what each species page entails, you can download a PDF sample of the book here.

Each species page contains information on one beetle species, so each open pair of pages features two species. From top to bottom each page has a generalized range map (entire world minus Antarctica mapped on each page) for the species; a table of generalized taxonomic and natural history information (family, subfamily, distribution, macrohabitat, microhabitat, feeding habits, and a note); a dorsolateral line drawing of the insect along with a note on the typical adult length (sometimes for both male and female if divergent); the species name in both italics and in all caps, along with the taxonomic authority and date; a paragraph on the natural history of the insect; a paragraph detailing related species of note; a photograph of the insect at actual size; a dorsal macro photograph, always of high quality; and a small figure heading next to the macro photograph with a bit more interesting natural history.

The level of detail in both the photographs and in the text is exceptional. For the photographs, you will have to look at the sample linked above to see what I mean. In terms of the text, each and every species is a joy to read about. For instance we learn about the cigarette beetle (Lasioderma serricorne; p.372) that specimens have been found in Tutankhamun’s tomb; and that the larvae of the Florida tortoise beetle (Hemisphaerota cyanea; p.555) build up strands of their own feces over their bodies to protect themselves from enemies. And on and on it goes, page after page in rich and amazing natural historical detail.

The book ends with several short appendices including a glossary, a classification of the Coleoptera, and a list of other beetle-based resources.

This is not the sort of book that most people would likely read through one page at a time front to back and then put away. Rather, it is a book that can be read much as one might open random drawers in an entomological collection, with the benefit of having a studied natural historian at your shoulder to tell you what you are looking at. In other words, this book is a sheer pleasure to read and to look at, and everyone will learn from it. It definitely belongs in the collection of every practicing entomologist or other naturalist who is interested in insects.