Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra

by Elena Johnson

2015, Gaspereau Press

48 pages

$17.95

One of my favorite poets, Dylan Thomas, once wrote the following in response to being questioned on his definition of poetry:

I, myself, do not read poetry for anything but pleasure. I read only the poems I like. This means, of course, that I have to read a lot of poems I don’t like before I find the ones I do, but, when I do find the ones I do, then all I can say is ‘Here they are’, and read them myself for pleasure.

…..

You can tear a poem apart to see what makes it technically tick, and say to yourself, when works are laid out before you, the vowels, the consonants, the rhymes or rhythms, ‘Yes this is it. This is why the poem moves me so. It is because of the craftsmanship’. But you’re back again where you began.

You’re back with the mystery of having been moved by words. The best craftsman always leaves holes and gaps in the works of the poem so that something that is not in the poem can creep, crawl, flash, or thunder in.

This has been my general approach to poetry over the years as well. Poetry is sort of like wine. You don’t need to explain why you don’t generally like Syrah, no matter the vintage, but can appreciate a good Merlot. When you find a poem or a poet or a school of poetry that rings for you, you will know it. Why? Because, as Thomas wrote, there is a “mystery of having been moved by words.” Elena Johnson’s “Field Notes for the Alpine Tundra” struck that mysterious chord with me. I suspect that this collection would have a good chance of doing that with any other naturalist who regularly engages in field work, whether on the alpine tundra or elsewhere.

I first noticed this book via a tweet from Nikki Reimer:

Today two caribou appear. / if these are the two I saw yesterday. / I haven’t seen four. — Elena Johnson

— Nik Reimes (@NikkiReimer) May 16, 2015

Three short lines – field notes, in fact. But lines that invoke an immediate image, right down to a slight chill in the air and the colorful lichens on the rocks all around. Reading those lines, I was drawn to that place, in that place.

This collection succeeds because, at its heart, it is all about place. In this case, the place is a research station in the Ruby Range mountains in the Yukon. Johnson spent a few weeks in 2008 there with several teams of scientists working out of the camp. The collection is a result of her time spent there and exhibits her abiding connection to the place.

The poems tend to be short featuring short – sometimes one-word – lines but containing intense imagery. There is not a poem in this book that would take you more than two minutes to read if you were to simply read it as you might prose and then move on. There is not a poem in this book, either, that will not cause you to linger and perhaps sip again like a complex Merlot. Each poem will provide a new surprise, a new flavor, upon second and further readings. In this way the poems are, indeed, field notes. Well-written field notes should contain substantial information in even a few words. These poems contain concentrated place-imagery, each word or short stanza bursting more detail onto the page with each reading than its short length belies.

Here is a stanza that many field scientists will appreciate (from “Topographic Map 115 G/1):

We hefted saws / and tubs and ropes / to drag it. / Slunk / through fog / in grizzly country / stopping briefly / to shout.

Lugging of miscellaneous field gear, the movement into the unknown, the heightened awareness, and the general silence of work punctuated by “hey bear” shouts. It is easy to feel like you’re right there, hoping that a bear is not ahead shrouded in the fog.

Or, in “Silent for the Dry Season”:

So little noise here; sound / becomes a feeling. My own blood / a humming constant.

This short stanza not only brings out the depth of silence that is encountered when we leave urban and even rural environments for the true wilderness (“sound/becomes a feeling), but Johnson’s choice of enjambment focuses the reader’s attention to the sound of their own heart ricocheting in their arteries. Silence is truly a reminder that we are alive, the counter-implication being that constant noise and distraction and resulting movement are, at times, more a pointer toward death than life.

A number of the poems are found poems taken from scientific field notes. For instance “Ptarmigan Observation Sheet” places five days of August field work – including time, GPS point, and behavioral details – into a poetic context. Those of us who take field (or lab) notes on a regular basis probably have never thought of our jotting to be poetic. Perhaps Johnson is suggesting that we rethink that. Reading our old notes should bring back images of what we saw, smelled, heard, did. Others reading those notes should have the same experience. Besides being drawn into a few days of ptarmigan life, this found poem also represents a lesson to field scientists. Specifically, if you begin think of your notes as poetry, you might take better notes.

Johnson’s book, as with any well-curated and well-edited collection, works as a larger poem in its entirety. The poems move in a series from first arrival to later departure. The first poem, “Mountain List” is a short four lines that indicate the author’s first impression of the “mountain lonely with sparrows.” Poems then range toward field work (including those found-poem notes) and losing count of time in day-to-day camp life:

I scratch lines onto a rock. / But I can’t remember if I marked yesterday, / if I already marked today.

In a poignant moment Johnson finds herself “Alone at the Base”:

The other tents / flap, flap, flap. No one / is ever coming back.

Is she worried? Or in some way wishing for deeper isolation? Or both?

The book ends with the author “Hiking Out”:

Two sandpipers clear / the brook’s edge, where / I tilt my bottle in.

The author drinks the last of the mountain and thus makes the alpine tundra a part of her, echoing the almost-eucharistic desire of field scientists to imbibe – and in a sense become a part of – their place of study.

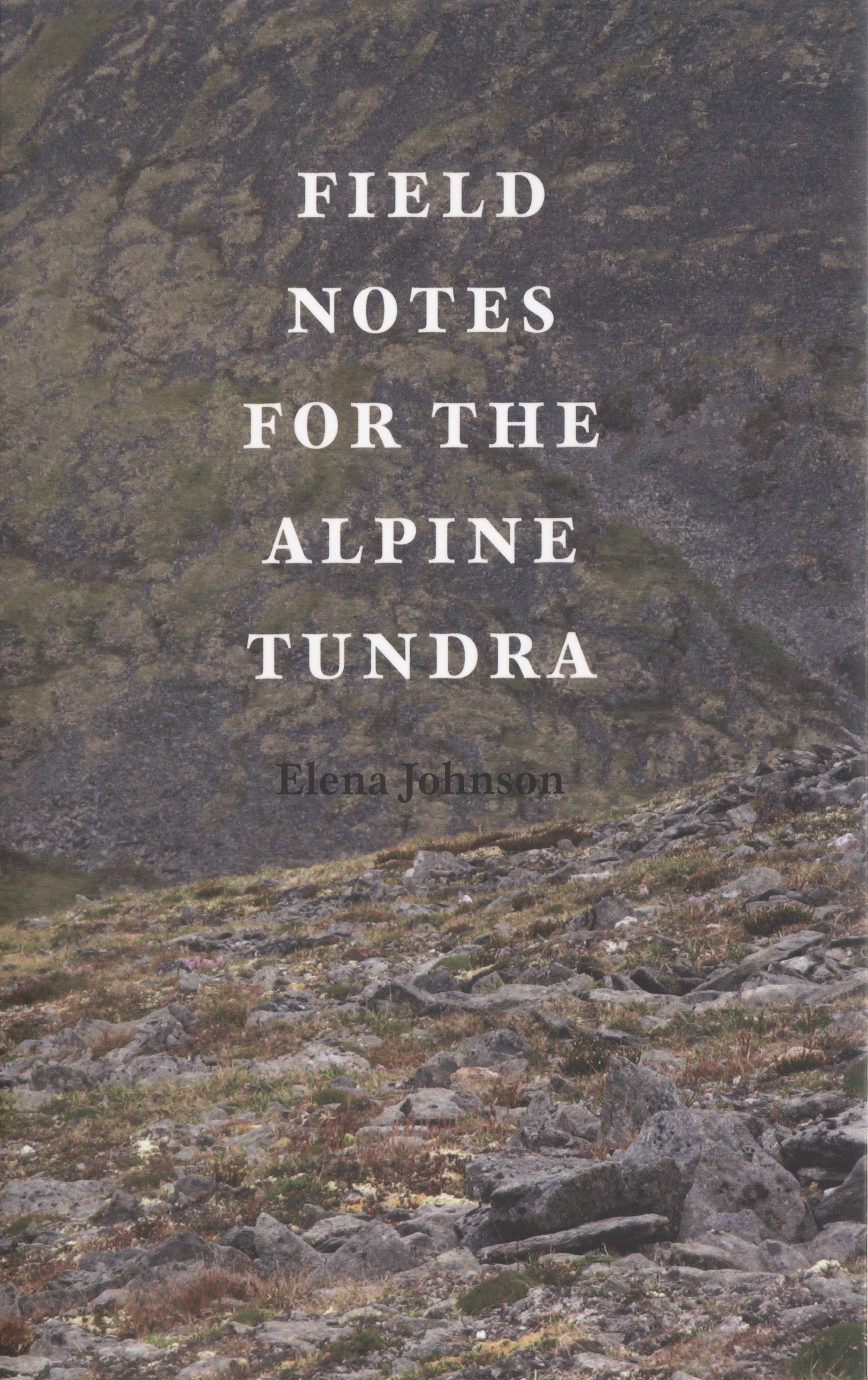

The physical book is a work of art in its own right. The jacket features, when entirely opened up, a photograph of two caribou appearing over a nearby lichen-encrusted ridge visualizing one of the poems. Remove the jacket, and you will find a grey-on-black repeated motif of caribou. The font – Mauritius, designed by Georg Trump – on rich ivory paper in a quality binding reminds the reader that this is a book to come back to.

I highly recommend that you read a few of Johnson’s poems from the book and – if the “mystery” of being “moved by (the) words” manifests – that you purchase the collection.