While many people don’t think about it too much, insects are extraordinarily communicative animals. Perhaps this tends to escape notice because, as with most animal communication, the “speakers” and “listeners” use forms of language that are wholly unfamiliar to us. Insects use chemical pheromones, vibrations in the air (sound) and through solids and liquids, visual cues, and touch. And oftentimes, just like we do when we talk and simultaneously gesture, they will use two or more of these methods at once to transmit complex messages.

While many people don’t think about it too much, insects are extraordinarily communicative animals. Perhaps this tends to escape notice because, as with most animal communication, the “speakers” and “listeners” use forms of language that are wholly unfamiliar to us. Insects use chemical pheromones, vibrations in the air (sound) and through solids and liquids, visual cues, and touch. And oftentimes, just like we do when we talk and simultaneously gesture, they will use two or more of these methods at once to transmit complex messages.

Bark beetles are no exception to this. In terms of chemical communication, they are one of the longest-studied insect groups. This is because learning how to mimic their chemical “words and sentences” can also help us to control their behavior. Bark beetles are an important part of any ecosystem in which they are found, but they can also be very economically destructive. They use their chemical language to, among other things, coordinate their often-fatal mass attacks on trees so that they can mate and their larvae can eat the tree’s tissues. Much of the research into bark beetle pheromone communication has been done with at least a background objective of developing new and better control methods. That is, if we can figure out how the insects are communicating with each other, we can send them false messages to lure them into traps, force them away from trees, or at least monitor their presence or absence in a forest or city park.

Bark beetles also “communicate” with researchers. One of the best things about working with this group of insects is that once they attack a tree, the parents and then the hatched brood etch their marks on the wood of the tree as they mine through the tissues just under the bark. The under-the-bark patterns of bark beetle galleries are about as diverse as the number of bark beetle species. In general terms, one or both of the parents excavate a main gallery, the female lays eggs on the walls of that tunnel, and then the hatched larvae bore outwards from the parental gallery. This means that an interested observer can strip back the bark of a tree – whether attacked recently or in the rather distant past – and can measure the length of the parental gallery and the length and number of the larval galleries. These measurements and counts give information on the number of eggs laid, the number of larvae hatched, and the success of the larvae among other things.

In other words, the beetles etch their story onto the wood, and we can read these “messages” as well as we can read a book.

Of course this isn’t real communication, per se, because the insects are not really passing a message on to the observer… or are they? Do the insects have something to say to us? What are they (collective) saying? These are questions Jody Gladding implicitly asks in her volume of poetry entitled “Translations from Bark Beetle”.

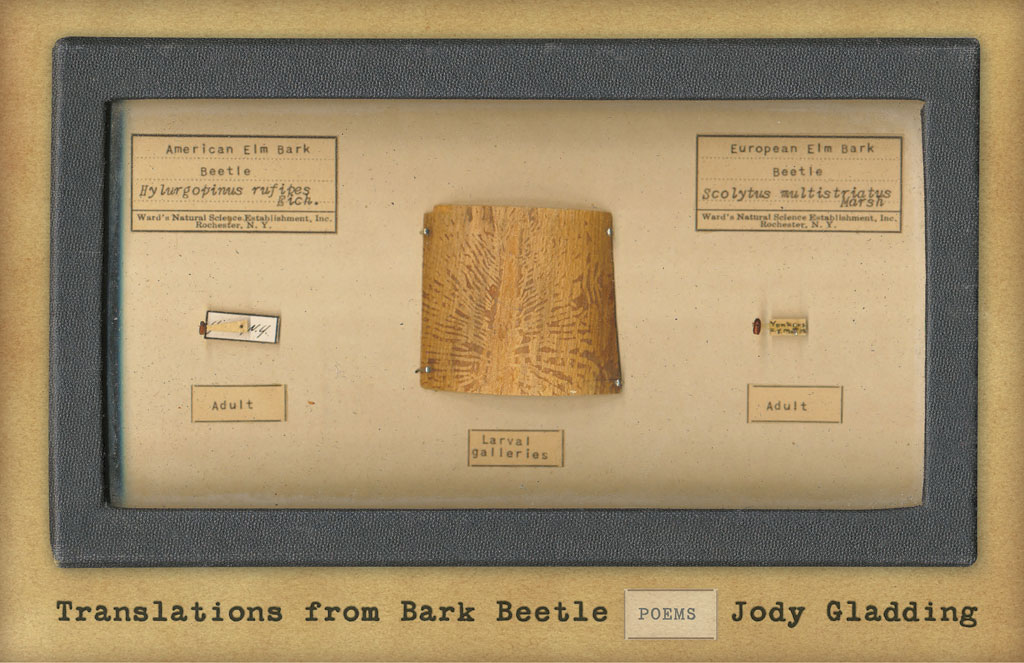

The cover of this book is the first thing that grabs the viewer – perhaps particularly if the viewer is an entomologist (click the thumbnail above to enlarge). The cover features pinned adult specimens of Hylurgopinus rufipes (a.k.a. the native elm bark beetle or the american elm bark beetle) and Scolytus multistriatus (a.k.a., the European elm bark beetle) along with an example of a bark beetle gallery etching. And this visual is the first poetic feature of the book. Here we see, juxtaposed, two insects that infest elms, but one that is supposed to be in North America sitting next to one that should never have arrived on our shores. The native elm bark beetle is a part of the system. While it can be destructive from a human perspective, it does what it has always done where it has always done it. The European elm bark beetle, on the other hand, is not supposed to be here, is not a natural component of the North American ecosystem, and is, if anything, even more destructive than its native cousin. The cover’s visual poetics, then, reveal that what we see as “natural” or “unnatural” (or “artificial”) may in fact have overtly similar symptoms, but that the deep reality differs in ways that matter.

And it is this deep reality that Gladding seeks throughout this volume. Bark beetle translations bookend this volume with a variety of other poems in between. In each case of bark beetle translation Gladding includes a rubbing of a gallery system and then provides the translation of the beetle-collective poetry. Gladding provides some indication of how she went about the translation, including this:

Certain elements of the grammar make translating Bark Beetle problematic. There are only two verb tenses: the cyclical and the radiant. Prepositional phrases figure prominently and seem necessary for a complete syntactical unit. The same pronoun form (indicated as •) is used for the first and second person in singular, plural, and all cases.

It is difficult – impossible, actually – to recreate any examples of the bark beetle poetry sufficiently in a blog format as the lineation necessarily follows the organized-but-chaotic shapes of the galleries. Certain sections stand out on their own, however, including this one from “Engraver Beetle Cycle”:

• think •’m repeating m•yself/there are rumors of flight and fungi/(of light and lying)/the death of a tree’s

“(R)umors of flight and fungi”… exactly what one might expect the yet-to-metamorphose larval collective under the bark to consider. This presents us with the question of what we (plural) contemplate in our (plural) larval stage, for ours is a continual procession of metamorphoses, whether we are willing to recognize that fact or not.

Ultimately the best way to appreciate the poems in their entirety along with the accompanying rubbings – besides buying the book, which I highly recommend you do – would be to take a look at a sample of the poetry linked at this page at Milkweed Editions. That short sample exemplifies the physical-natural aspect of Gladding’s poetry. In other instances she creates poems on objects – natural and artificial – ranging from eggs to tongue depressors to slate to change-of-address forms. This interplay between natural and artificial is a theme throughout the volume.

Some, maybe many, of poems seem playful on first glance – for instance “quarrying” poems from Robert Frost – but contain a poignant, serious depth that is apparent with close contemplation. While this entire volume could be read in one sitting, each piece could, and should, be chewed and digested slowly, slowly. To riff on the natural/artificial divide, this volume is not a Big Mac that you devour in a rush. Rather it is a hearty soup and fresh bread eaten alongside conversation with good friends and a bottle of fine wine.

I will close by pointing to one of my favorite poems in this excellent collection. In “Look Inside to See if You’ve Won” Gladding shines a glaring light on the uncaring effect of human artifice on the natural. Describing blundering cars, big box stores, and fast food in the midst of a flight of butterflies being crushed on radiator grilles she writes:

The butterflies were not trying to tell us

anything and anyway we wouldn’t have noticed. It was

such a pretty drive.

If you think that short passage stings, buy the book, slowly chew that whole poem as a bark beetle would work its way through the tissues of a tree. And then go on to digest the rest of them. Slowly, slowly.

Translations from Bark Beetle, by Jody Gladding, is published by Milkweed Editions and is available from Milkweed Editions, your local bookseller, or various online sources. A Q&A with Jody Gladding, along with links to further written and spoken examples of her poetry, can be found at the book description page.